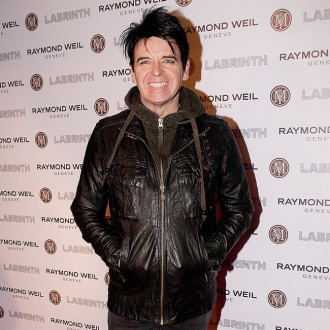

Review of Replicas, Telekon & The Pleasure Principle Reissues Album by Gary Numan

Shot on the front of Replicas, Gary Numan look much like the embodiment of Bron Helstrom, the former male prostitute of Samuel R. Delaney's pan-cultural science fiction novel Triton. Hair peroxide blond and clad entirely in black, the man born Gary Webb stares into the middle distance in a room illuminated by a single, naked light bulb. Out of the window is The Park, an area much like the lawless free zones a citizen can choose to live in as part of Delaney's ultra-liberal futuristic society.

Both the image and Helstrom's character are highly ambiguous, avatars of a 1970's in which computers and the cold war were melding science fact, in which paranoia and the boundaries of sexuality, personal politics and our mechanistic existences began to dissolve. A dystopianly themed concept album, in musical terms Replicas came heavily influenced by Low-era Bowie and perhaps less fashionably, the chugging guitars of glam. Numan had discovered synthesizers by accident during its recording process and experienced a career changing epiphany in the process, one which gives the only Tubeway Army album some odd juxtapositions. On songs like Praying To The Aliens, The Machman and You Are In My Vision for example the emphasis is on arty, post-punk atmospheres, the singer's atonal voice providing a monotone cyborg appliqué.

The master stroke however came in bringing the doom-soaked Moogs to the forefront, either on filmic instrumentals such as I Nearly Married A Human or When Machines Rock, but especially in the claustrophobic Down In The Park, or the album's focal point Are Friends Electric. A surprise number one at the time, the latter was both maudlin and authoritarian, Numan forlornly seeking empathetic love from an emotionless machine, vulnerable flesh and blood in a world of hard wired logic.

Solo - or at least ostensibly so, having ditched the Army - on 1979's The Pleasure Principle the high concept moved on to embrace keyboards en masse, creating in the process synth pop without the pop, a loveless hybrid which mixed the paranoid aesthetics of Room 101 with bleak, rhythmic austerity. It's mood was unrelenting, enveloping: only on the swinging Trojan horse of a single Cars did anybody feel they could do anything as rebellious as dance. In it notes sounded like air raid sirens and robotic handclaps crashed like breaking glass; it's the first and probably best song of its kind, third millennium disco for people who were still listening to the Bee Gees. Inevitably it also pushed it's companions back into relative obscurity, a fate which the wistful, electric violin led vulnerability of Complex scarcely deserved, whilst in the proto-industrial grains of Metal a thousand Front 242's were seemingly born.

Released just 12 months later, Telekon Numan declared marked the end of the "Machine" phase of his career: now the reluctant subject of a personality cult, he found himself having to cope with the very 20th century pressures of fandom and expectation. Alongside this a revolution was occurring in the guise of acts who didn't see their technology as a tool of dancefloor oppression: through acts like The Human League and Depeche Mode it was starting to become apparent that it was possible to make sounds using it which were harmonious, melodic even. Not that this seemed to concern him particularly, indeed both of Telekon's preceding singles - We Are Glass and I Die:You Die - were by now instantly recognisable by their slightly histrionic shorthand. On arrival though it became apparent there were some subtle new dimensions - witness the wry lyrical stardom commentary on Remind Me To Smile (And it's modish plucked bass) - whilst in the eccentric piano breakdowns of the title track there was a less totalitarian air.

Of the three, Telekon is also the only release here to get a sprinkling of the much-dreaded additional material - alternate takes of Remind Me To Smile, I Die:You Die and less obviously Down In The Park - plus a curious but beguiling version of Satie's Trois Gymnopeides along with b-side fodder A Game Called Echo and Photograph.

Now re-issued on 180g vinyl, two thoughts strike us at Contact Towers. The first is that given the obsessional nature of Numan fans it's unlikely that any of the material here hasn't been traded or bootlegged amongst them in some form, even if the format is now so modish. The real reason to absorb this triptych then for the newcomer is to consider the influence it had on a generation of disaffected artists (The most well-known being Trent Reznor), who took it's extremes and invented new, more extreme and alien constructs out of them. Appreciated in this way, it's still possible to find a reason to ignore the cynicism surrounding their re-appearance and interpret them less fundamentally, as compelling artefacts of a bygone era when robots made cars but artificial intelligence was still the stuff of fiction.

Official Site - http://www.numan.co.uk/